City of Durham Fleet Management

The city of Durham Fleet Management department finds a balance between cost and supporting public services.

By Tim O’Connor

Municipalities needs vehicles to deliver the services residents have come to expect, but they also need to keep budgets in check. With the average cost of a fire engine nearing $500,000 – and sometimes more – a one-time purchase can make a significant dent in a municipal budget. Cities such as Durham, N.C., are increasingly relying on their fleet management departments to balance equipment and vehicle needs with available funding.

“We are the gatekeeper,” says Joe Clark, fleet management director for the city of Durham, which manages 1,700 vehicles, including police squad cars, fire trucks, backhoes, solid waste trucks and sewer vacuums.

Before committing to the purchase of a new vehicle, Clark’s team works with the department that will operate the truck, car or piece of equipment to determine precisely what capabilities they need. “What we do before we buy any vehicle is sit down with the department and look at what the mission is,” Clark says.

Once it defines those specifications, fleet management reaches out to manufacturers to find the right vehicle for that use, protecting taxpayer dollars by avoiding upcharges for bells and whistles that aren’t needed.

In identifying the best vehicles, Durham Fleet Management considers factors beyond the upfront purchase price. The department looks at total lifecycle costs, cost per mile, service delivery metrics and utilization to make data-driven decisions.

Standardizing Parts

One of the most important variables in Durham’s cost-to-own equation is the cost of maintaining its vehicles. To reduce upkeep costs and make it easier to get assets back into operation, the department favors purchasing vehicles that share common components, such as the emergency lights on police cars and fire trucks.

That makes it easier to stock parts and train technicians because there is more familiarity across the board. “We’ve got a standardization model,” Clark says. “If we’re buying the same chassis and brakes, at some point you’re going to have some economies of scale on the maintenance side.”

Durham works with OEMs to ensure their vehicles support those interchangeable parts. The police department, for example, is moving to one vehicle make across marked and unmarked squads. When choosing that make, Durham’s fleet management team coordinates with the manufacturer to identify a vehicle that is suitable for both roles.

Standardization makes sense from a maintenance cost perspective, but it also creates a risk of being left behind as technology advances. In pushing for standardization in parts, Durham’s fleet management department is careful not to do so at the expense of capability. In cases where components have become obsolete, the department is open to finding opportunities with other OEMs that can provide the equivalent up-to-date vehicle or piece of equipment.

Preventive Maintenance

Once Durham Fleet Management selects a vehicle make, the department shifts its focus to ensuring that truck or car operates with minimal downtime. Depending on the vehicle and its frequency of use, the department performs routine maintenance inspections as frequently as every few weeks. The checks can cause some disruption for the department the vehicle is assigned to, but Assistant Director John Ferguson says it’s better to do regular preventive maintenance than to risk a bigger problem that takes the vehicle out of service for a longer period of time.

The regularity of those inspections also gives the department better telemetric data on how the vehicle is being used. If one car’s cost-per-mile to operate is abnormal compared to other vehicles in the same class, Durham Fleet Management can flag that car and look at the data to determine why it needs more frequent maintenance or is using up more gasoline. If the problem is found across multiple vehicles, the department can contact that manufacturer to determine if there is a more widespread issue that would be covered by warranty.

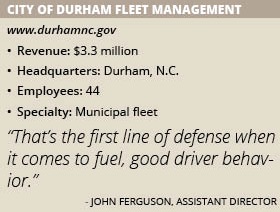

More often than not, driver behavior is the culprit. “That’s the first line of defense when it comes to fuel, good driver behavior,” Ferguson says.

To curb those outliers, Durham Fleet Management is working with other city departments to educate drivers on limiting idle time by remembering to shut off the engine when the vehicle is not in use. Stickers have also been installed on vehicle windshields to remind drivers to turn off their vehicles and the department is adopting technologies that will automatically shut down engines of heavy vehicles such as garbage trucks after five minutes of inactivity. It has also installed auxiliary power units on fire trucks that will reduce fuel consumption when emergency vehicles are idling during a response call.

Reducing idle time not only improves the cost-per-mile of vehicles, but it fits into Durham’s larger environmental goal of reducing fuel consumption by 20 percent from 2017 levels by 2020. “At first glance, it’s aggressive and garners some attention and puts pressure on the people within the departments to achieve those goals,” Ferguson says.

Another way Durham is reducing the lifetime costs of its vehicles is by switching to a take-home car model for its police vehicles. In many municipalities, police vehicles make up a huge portion of the fleet budget because of the high number of vehicle and the frequency of their use. Towns that run pool cars, in which officers will share the same vehicle over several shifts, tend to see much higher maintenance and shorter lifespan costs because the vehicles must run 24/7.

Assigning an officer to a vehicle that they take home with them increases the size of the fleet, but the vehicles tend to last much longer because they experience far less wear and tear. “If operators have assigned vehicles they tend to take better care of those vehicles,” Ferguson says.

10-Year Plan

Durham Fleet Management’s efforts during the past few years have earned it the Leading Fleets Award, sponsored by Government Fleet Magazine, and recognition from the 100 Best Fleets Award program. Its standing as one of the top municipal fleet management departments in the country helped it to persuade Durham elected officials to approve a 10-year funding plan in 2016 for scheduled vehicle replacements.

Like many municipalities during the Great Recession, the city of Durham put off many vehicle replacements in the late 2000s as a way to trim the budget. However, that left many vehicles operating long past their expected lifespans and the replacement schedule still hasn’t normalized in the years since the economic recovery began.

That ultimately effects city services. Durham has two leaf vacuums so if one goes down because of age and excessive ware, the city has only 50 percent capacity for leaf removal and might not be able to clear streets before winter sets in. Likewise, if an old fire engine fails, it can delay emergency response times for an entire section of the city. “If they can’t complete their mission, we’re a failure,” Clark says. “We’re part of that.”

The decade-long funding plan totals $56 million from the city’s general fund and aims to get those replacements back on a normal schedule. “If we can make it through 10 years we should be whole,” Clark says.