Revolutionizing Electric Trucks: Innovation and Patent Insights in the EV Haulage Sector

Something old, something new… Callum Wardle looks at innovation in the electric truck arena

Whilst growing demand for battery electric passenger cars has captured most of the headlines recently, a quiet revolution is already underway in the development of next generation electric trucks.

The environmental benefits of zero-emission electric trucks are self-evident – both in terms of their impact on global CO2 emissions and their ability to reduce road-side local emissions. However, there are significant commercial benefits too for haulage firms and transport operators. As the technology improves, the total cost of ownership for electric vehicles becomes less than for conventional ICE-powered vehicles, due to improved reliability and reduced servicing costs of electric drivelines. Improved vehicle performance also becomes a factor, as the typically high torque of electric drivelines exceeds that of similarly-sized ICE trucks.

Electric delivery vehicles are not a new concept. The classic example is the milk float. Perhaps less well known is the use of electric refuse trucks, which were first used by Birmingham City Council in 1918. More recent  new entrants to the market are Arrival and Volta and both have partnerships with well-known delivery companies to provide electric vans and trucks.

new entrants to the market are Arrival and Volta and both have partnerships with well-known delivery companies to provide electric vans and trucks.

This ‘reinvention’ of established ideas is evident in a recently published patent application US2020/0247224, filed by Daimler AG. This application addresses the issues of efficiency losses and unsprung weight in the electric driveline for larger electrically-powered commercial vehicles. To date, two main concepts have been employed to electrically drive larger trucks. An electric motor, often in conjunction with a simple gearbox, is used to drive a conventional axle-mounted differential via a propshaft. Alternatively, individual wheel-mounted motors are used to directly provide drive to the wheels. In the case of the former, transmission losses are still incurred through the propshaft, whilst in the latter case the unsprung weight of each wheel and associated motor unit is greater.

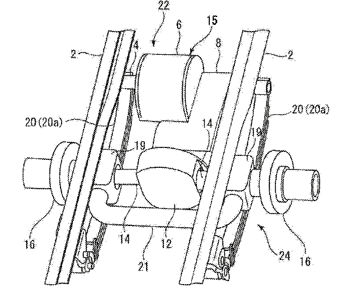

Daimler AG addresses these issues by mounting a fully integrated motor (6), gearbox (8), and differential (12) as a unit to the chassis rails (2) of the vehicle. Driveshafts (14) are connected between the differential and respective wheel hubs (16), via flexible, universal joints. Each wheel hub, and associated stub axle, is suspended from the chassis using respective leaf springs (20) and are connected together by a hollow element (21), in an arrangement known as a ‘De Dion tube’.

This arrangement has a number of advantages. Transmission losses are reduced by eliminating the propshaft and, by mounting the drive unit to the chassis, unsprung mass is reduced in comparison to individual in-wheel motors.

At first appearance, there is nothing radical about this proposed arrangement. De Dion suspension can be traced back to the early 1900s and also made more recent reappearance in the original Smart car, also manufactured by Daimler. However, the inventiveness of this patent application lies in the combination of an electric drive unit, including differential, which is mounted to the vehicle chassis and the separate suspension of the driven wheels.

This illustrates a potentially important consideration for innovators in the electric truck space in that combinations of sometimes well-known technologies may still be patentable. This means it is possible to prevent, or at least deter, competitors from closely following the same design path by protecting some of these combinations as they are found. In a relatively new market, where the optimum design is still not settled, the ability to claim a particular design route as your own could be a key market differentiator.

One potential barrier to identifying such ‘combination’ inventions can be ‘invention blindness’. This is where once a design has been proposed, those involved tend to dismiss it as being obvious. Involving a trusted adviser at regular intervals during the design and engineering phase can help to ensure patentable inventions are properly captured.

Callum Wardle is a partner and patent attorney at European intellectual property firm, Withers & Rogers.

www.withersrogers.com